On a historic, attractive street in Manhattan’s West Village – the kind that feels like a film set – 6a architects has completed its first US project to date, the Center for Art, Research and Alliances (CARA). The practice took a brick and concrete warehouse constructed in 1909 – originally used to store playing cards – and transformed it into a home for a new non-profit art centre, research institute and publisher. In typical 6a style, original building details are honoured, unnecessary interior finishes have been stripped back, and spaces have been designed to be open and flexible. ‘The building has its own personality, but is porous at the same time,’ says Manuela Moscoso, CARA’s executive director. She believes the building has contributed to shaping the organisation itself.

And for 6a, deciding to do the project was a ‘no-brainer’, says founding director Tom Emerson. ‘We’ve loved New York for a long time. When this came along we were super excited, because we could get to work with conditions – social, urban, architectural – which we had always enjoyed observing and experiencing but had never had a chance to really interact with at an architectural level.’

The story of CARA began in 2015, when founder Jane Hait – a former gallery owner – began to think about what kind of cultural organisation New York might need. The seed for a space where justice and equitability could be built through arts was planted, and a building was subsequently secured. Although Hait had been looking for something with a more domestic feel, she discovered the former warehouse ‘by happy accident.’ She says: ‘It has incredible bones, it’s very robust. It could do the things we wanted it to do.’ What’s more, the building’s brick street frontage fits seamlessly into the surrounding rows of townhouses, matching this more domestic proportioning Hait was after. ‘It was intimate, warm and approachable, but also super flexible’ she says.

Hait turned to 6a having long admired their work for art spaces including Raven Row and Sadie Coles HQ in London. Conversations began in late 2016, design work started in early 2017 and construction began in December 2019 – and was obviously disrupted by the global pandemic. ‘It was built over FaceTime’ laughs Hait. After a series of ‘soft launch’ events over this summer, the centre officially opened to the public in October.

Entering the building, 6a’s main intervention to the facade was to replace a wooden door and garage roller shutter with two large window openings, with thin metal grid framing and inbuilt doors. These glazed openings welcome both daylight and visitors into the first space, the open-plan bookshop, which has been fitted out with playful, colourful elements designed by Studio Manuel Raeder and Rodolfo Samperio.

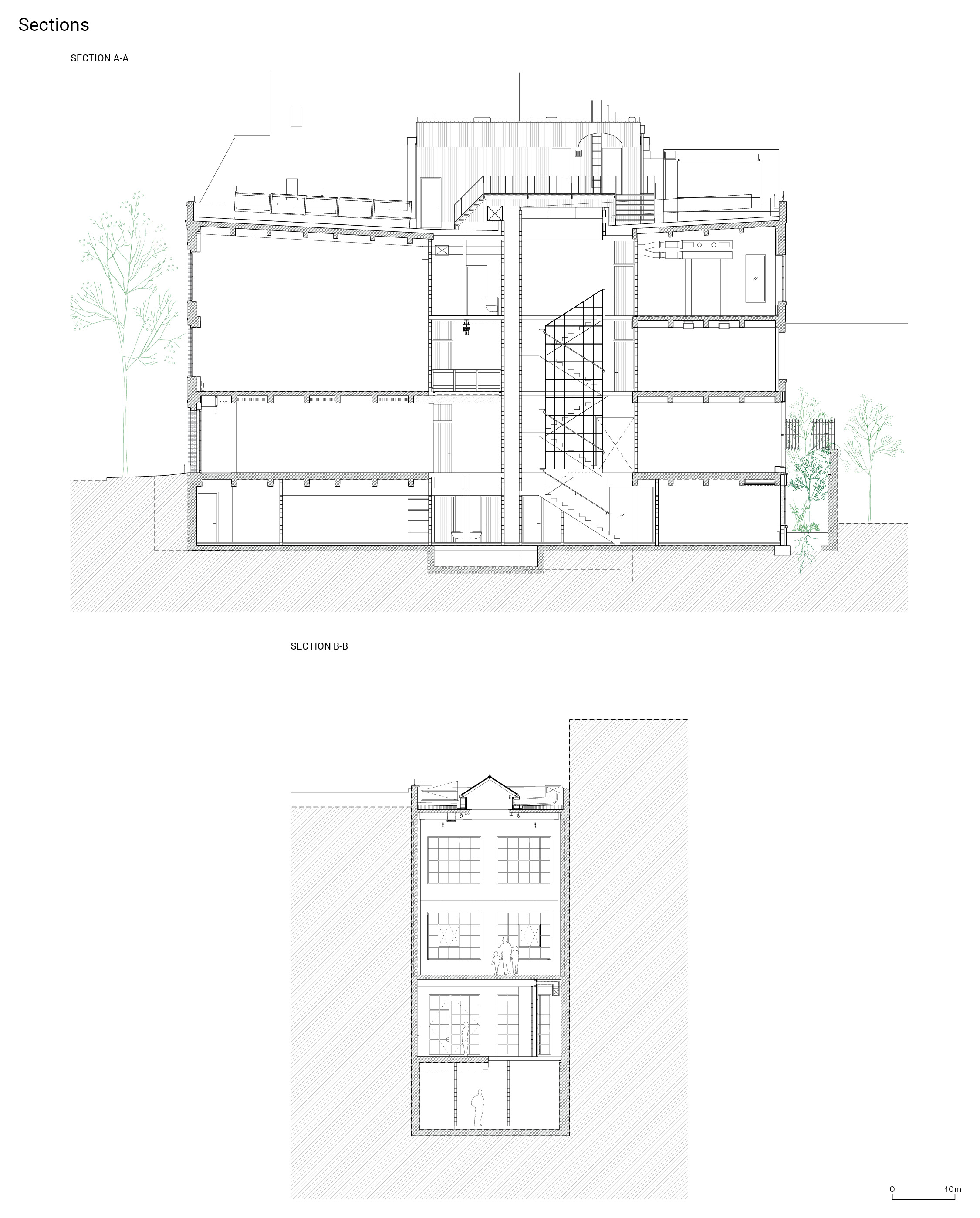

Beyond this, visitors walk through the core of the building towards the rear exhibition space. This core, notably, had to be fully replaced in order to meet strict code regulations. The main staircase – originally in cast iron, but too narrow for fire safety – was fully replaced with a new poured concrete stair; structural walls were replaced with CMU (concrete masonry unit) blocks, floors replaced with newly poured concrete. The large elevator was moved and another fire staircase was added. Despite being a whole new part of the building, the feeling is raw and industrial, matching the structure’s past.

Entering the rear exhibition space, there is a show-stopping window wall, echoing the entrance, looking out on to a slim excavated garden and neighbouring courtyard beyond. There had originally been four vertical windows on this back wall, and 6a replaced them with this generous opening, letting in light and creating an engagement with the surrounding urban fabric. ‘We were really keen that the whole building – galleries and non-gallery spaces – feel connected to the city,’ explains Emerson. This suited Hait’s vision, which was to avoid the creation a ‘white cube box’ blocking out the outside world.

In this ground-floor exhibition space, 6a removed flooring that had been added in the late 20th century – the building went through various iterations as offices and studios – revealing the original, robust yet visibly worn concrete floor below. Paint covering the concrete ceiling was also peeled back, allowing the material to speak for itself.

Moving into the new staircase, one can ascend down to the basement level – housing offices, storage rooms and public bathrooms – or up to further gallery spaces and private offices beyond. In this stairwell, 6a has added a crowning skylight which bathes the space in natural daylight. ‘We really wanted to try and bring as much light through into that space as possible,’ says Emerson. This is complemented by two strategic windows in the side wall of the stairwell, giving glimpses out to sky and city to maintain that sense of embracing the building’s context.

The stairwell is also notable for a glass partition that rises up through the centre, repeating the motif of the window walls with its thin metal grid. ‘We had been doing a lot of studies with this thin metal glazing,’ says Emerson. ‘At some point we thought, this looks light and very elegant, why don’t we just raise a window all the way up the centre of the stair? It somehow felt like it was connected to other parts of the building, and was also quite special and unusual.’

Down in the basement, the rear office space has been given new windows where previously they were none, made possible by excavating the ground down to this level. The office subsequently looks out on this slim excavated space, turned into a small garden with the help of Dan Pearson Studios. Elsewhere at basement level, the public bathrooms are found, and here is where 6a’s dominant stripping-back approach is counterbalanced with playful insertion. The two bathroom interiors are clad almost completely in polished granite. ‘The bedrock of Manhattan is granite,’ notes Emerson, adding that inspiration was also taken from original blocks of granite positioned outside the building entrance. In these granite-immersed bathrooms – the stuff of drooling Pinterest boards and Instagram posts – pops of colour (another 6a classic) appear in the form of bright red taps and detailing from Vola.

Another playful addition at this basement level is a sculptural water fountain designed by 6a, which appears as an art installation in itself, with looping pipes. ‘It’s part plumbing designed by us, part code – in public buildings [in the US] you have to have two water fountains at different heights – and part reclaimed ceramic basin that we found. The whole thing is a little sculptural collage of bits,’ says Emerson.

Ascending back up the main staircase, you reach the first floor, where the main gesture and heart of the building is: a double-height gallery space. It packs quite the punch. Four large square windows, along with a skylight, flood the space with natural daylight. 6a carefully configured the space for maximum impact: there had been a wraparound mezzanine balcony added in the 1990s, which the practice removed. Wooden window frames also added at this time were replaced with metal grid frames, in keeping with the glazing throughout the building.

At the rear of the first floor is a smaller, single-height exhibition space, echoing that on the ground floor. But here, the original windows on the back wall have been filled in for structural reasons, with a new large square window opening created in the side wall.

On the top floor – not open to the public – the fit out is still taking shape, but this will be dedicated to offices – lit generously by both the original four back-wall windows and a new large window in the side wall – as well as a kitchenette and bathroom.

As a whole, 6a wanted the building to be defined by flexibility. ‘We were really interested in a building that could be written and overwritten many times,’ says Emerson. “The kind of organisation that Jane [Hait] was describing was the sort of thing where probably the only thing you can be certain of is that [the space] will be used in ways you couldn’t possibly imagine. So we were really interested in a project where the spaces are good enough that they could be reinvented by people over and over again.’

Walking back to the entrance of the building, the bookshop is bustling, with a visit from a student group deep in discussion. It’s clear that CARA is a space for art, yes, but primarily it is a space for people. Its industrial aesthetic might void it of a little cosiness, but the good thing about 6a’s stripped back, adaptable spaces is that – as Emerson notes – they can transform for whatever purpose is needed.

Returning to the street, you realise how subtle CARA’s urban presence is. It doesn’t announce itself in a loud fashion but this is an organisation – and a building – that is not about shouting. It centres on listening, opening and adapting, with one foot in history and the other confidently stepping towards the future.

Francesca Perry is a London-based editor and writer specialising in journalism centred on design, cities, architecture, sustainability and culture

Architect’s view

The project’s principal sustainable measure is the reuse and deep retrofit of the existing building. Significant embodied carbon savings were achieved following a detailed appraisal of the building fabric, which resulted in the retention of building structure, floors and facades. The introduction of new resources is minimised through the reuse and refurbishment of existing features and minimal finishes. Continuity of history and building culture are visible in traces of former constructions throughout the fabric.

Upgrade of the building fabric through high performance insulation (recycled and organic where possible) and window replacement limits long-term operational emissions by reducing heat-loss and lowering demands on the heating-cooling systems.

The services, which provide an internal environment suitable for a New York gallery, balance ultra-efficient technologies with passive environmental measures. In the former, an AHU with RTU Heat Recovery and low-energy LED lighting reduce grid energy demands, and BMS Control allows the organisation to monitor and improve performance to meet their energy targets. A hybrid mechanical/natural ventilation strategy, coupled with high thermal mass, means that the gallery can be operated almost entirely passively during ambient seasonal temperatures. The design maximises natural daylight for the organisation’s diverse programme, retaining the large window and rooflight openings and introducing a large new opening at the first-floor gallery.

The rear garden, designed by Dan Pearson Studio, includes mature trees and a varied planting scheme, which enhances ecology and biodiversity. The garden becomes a visual amenity to the gallery visitors, as well as an outdoor space for the staff to enjoy.

Tom Emerson, director, 6a architects

Client’s view

When embarking upon our collaboration with 6a architects to design what is now the Center for Art, Research and Alliances (CARA), we were drawn to their light touch. We didn’t want to impose a look or feel on the building, we wanted to allow its history and materials to speak. We imagined something slower, warmer, and more textured—a welcoming space that cares not only for art objects, but for people and their practices. As an arts nonprofit, research centre, and publisher, we needed flexible spaces for public programs, research, and exhibitions. It also felt important to convey the history of the building, a former playing card warehouse with an industrial past; 6a did this by revealing traces of the original walls and exposed slabs and took care not to cover structural elements unless it was functionally necessary.

In addition to 6a’s climate-conscious ethics, as well as the project itself being a historical re-use and therefore lower impact, we worked with sustainability consultant Art to Zero to identify areas where the building could be more efficient. Insulation of the external envelope, new roofing insulation, window selection, thermal upgrades, and a heat recovery system were among the environmental considerations. CARA exists in dialogue with its surrounding context, and the building maximises daylight and views to the street and sky, ultimately reflecting the organisation’s porosity. It is a place for coming together and learning and unlearning, and the ways in which the interior connects visitors to the outside world underscores this mission.

Jane Hait, founder, and Manuela Moscoso, executive director and chief curator, CARA

Engineer’s view

The existing building’s original use as a factory with its generous load allowances provided the ideal opportunity to repurpose the spaces into a sustainable new flexible gallery space. The design intent was to retain and expose as much of the original structure as possible, while meeting code requirements and extending the design life of the building.

To facilitate a new circulation core to provide two means of egress and a new elevator, the central portion of the building was demolished and rebuilt in reinforced concrete masonry and concrete flat slabs. The new construction was tied into the existing concrete-encased steel girders and concrete floors, which were all left fully exposed. Repairs were only carried out on the original structure where absolutely necessary for structural integrity and durability. The newly excavated rear yard, which required underpinning of several adjacent properties, provides a pocket of green space within this densely built-up area of Manhattan.

As the multidisciplinary engineer, Arup worked closely with 6a architects in coordinating the building services, which remain exposed throughout and are expressed within the spaces. Fire suppression systems, ducts, conduits and other typical code-required elements are all on show and celebrated, rather than being hidden behind finishes. Efficient new building mechanical systems and upgrades to the existing fabric ensure that the spaces remain comfortable during New York City’s harsh winters and hot summers, optimized for energy efficiency. Natural daylighting is maximized throughout the building, supplemented by efficient and flexible gallery lighting systems.

Alex Reddihough, senior engineer, Arup New York

Working detail

New York building code is particularly stringent to a UK or European architect. The combination of tall buildings and a relatively recent history of intense urbanisation creates extremely exacting regulations.

A new lift core and two stairs were inserted into the central portion of the building to meet New York’s fire code and establish universal public access. The process of stripping out the existing revealed the original structure and opened up alternative spatial proportions within the building. The stair and core celebrate the city’s materiality and building culture with a reduced material palette of New York vernacular; CMU (NY concrete block) and exposed services next to historic fabric, with traces of the former steel structure still visible in the brickwork. Carefully arranged by trade, exposed services describe the workings of the building, with radiators, conduits, sprinklers and ductwork becoming characters within the space.

A glazed steel grid rises the height of the stair forming a guardrail between adjacent flights, echoing the original gridded concrete floors in the galleries, the new windows, and the grid system of the city itself. Welded together on site and hand painted in white gloss, the bent continuous handrail and brackets embody the craftsmanship of Brooklyn’s makers. In situ concrete treads are nosed with waxed mild steel, evoking the robust kerb detailing of the city’s sidewalks, polished through use.

The stair is lit by windows at each level and a large skylight above. At the top floor, a granite seat offers CARA’s team a quiet place with a view through the gardens of the city block and a landscape of New York rooftops.

Tom Emerson, director, 6a architects

Project data

Start on site: January 2020

Completion date: July 2021

Gross internal floor area: 795m²

Construction cost: Undisclosed

Architect: 6a architects

Client: Center for Arts, Research and Alliances

Executive architect: 20X Architects

Structural engineer: Arup

Cost consultant: Cost Plus

Project manager: Paratus Group

Expeditor: Agouti Construction Consulting

Landscape designer: Dan Pearson Studio

Bookstore designer: Studio Manuel Reader and Rodolfo Samperio

Visual identity and wayfinding: The Rodina

Wayfinding: David Reinfurt

Acoustic consultant: Arup

Metalwork: HMH, New York

Main contractor: Eurostruct

CAD software used: MicroStation, Rhino

Annual CO2 emissions: Not supplied (building not quite complete)