Last week it emerged that Arney Fender Katsalidis (AFK) had submitted plans on behalf of Schroders Capital Real Estate for a 285m-tall office tower at 55 Bishopsgate.

The £600 million scheme, on the western edge of the Square Mile’s growing high-rise cluster, would replace a 10-storey 1992 building designed by Fitzroy Robinson.

The heritage campaign group described the existing block as a ‘sophisticated commercial building with high-quality finishes and detailing’ which ‘draws on and reflects’ the Mewes & Davis 1920s Grade II-listed Hudson Bay House opposite.

The listing bid is supported by architect John Robertson of John Roberston Architects, who was partner in charge at Fitrzoy Robinson during the design and delivery of 55 Bishopsgate.

In a letter shared with the AJ (see below), Robertson said the original building had been conceived as ‘a loose fit and flexible design, easily capable of retrofitting and extension’ and branded AFK’s proposals ‘harmful’ to townscape views.

AFK’s proposed skyscraper, together with a linked 22-storey block, would provide about 74,000m² of office space as well as ‘expansive’ public space on the top floor – dubbed the ‘Conservatory’ – and activation at ground level.

If completed today, it would be the UK’s third tallest building in the UK behind The Shard by Renzo Piano Building Workshop, the current national record holder at 310m AOD, and the neighbouring 22 Bishopsgate (295m AOD) by PLP, the highest completed building in the Square Mile.

The AFK scheme would sit between Richard Seiffert’s NatWest Tower (Tower 42) and GMW’s 99 Bishopsgate.

According to the Twentieth Century Society, the design team behind the original 55 Bishopsgate office had ‘decided against building a tower on the site and instead built at a more modest scale to provide … some ‘breathing space between the two towers’.

The society said the design team had been influenced by the ‘stripped Classical design’ of Otto Wagner, with its ‘language of panels and joints’ evoking his Austrian Postal Savings Bank in Vienna (1906).

The society’s listing application to Historic England cites a number of contemporary critics writing around the time 55 Bishopsgate was completed. It quotes John Wrothington, in Architecture Today in 1992, saying: ‘55 Bishopsgate is an asset to the City of London. It brings dignity back to Bishopsgate, provides a continuity of streetscape and offers both framed vistas and enjoyable fragmentary details.’

The application concludes: ‘In our view, [the building] has national heritage significance and should be statutory listed to prevent its demolition.’

Historic England confirmed it had received the listing application and that, having been consulted on the AFK proposals, was carrying out its ‘initial assessments’. It is understood the main heritage issues are likely to be the impact of the proposed tower on the protected views out of St James’s Park and of St Paul’s Cathedral from Waterloo Bridge.

According to the AFK team, the tower will be ‘one of the first all-electric tall buildings in the UK in both power supply and standby generation’. The designers also claim refurbishment of the existing 30-year-old Postmodern block was ‘not considered to be feasible’.

Instead, there would be a focus on ‘minimising the carbon impact of the new development’, by reusing existing materials. A pre–redevelopment audit also identified ‘potential uses, markets and targets for anticipated waste streams [to] maximise the value of the existing materials and components’.

In response to Robertson’s letter, AFK founder Earle Arney insisted ‘a retrofit could not be justified, given the way in which the City and the rapid advancement of both technology and city-making approaches since the completion of the existing building’.

Arney (see letter bottom), added that a Heritage, Townscape and Visual Impact Assessment demonstrated the proposed tower would ‘not result in unacceptable harm to the historic environment and will also deliver significant townscape and urban design benefits that will contribute to the vital activities of London’s commercial centre’.

Subject to approval, the scheme is set to complete in 2030.

View of existing office building at 55 Bishopsgate, which would be demolished to make way for the new tower:

Letter to the AJ by John Robertson

I was disappointed to read last week that a planning application has been submitted to The City of London for the demolition of 55 Bishopsgate and for its replacement with a 63 storey tower by architects Arney Fender Katsalidis.

As signatory to the AJ’s Retrofirst campaign, I feel it is important to write about this planning application, which would demolish a 30-year-old office building, designed in the 1980s as a loose fit and flexible design, easily capable of retrofitting and extension. For example, the existing building is designed with a 9m x 9m structural grid and with floor-to-floor heights varying from 4.030m to 4.580m. (The floor-to-floor heights of the proposed tower are 3.950m). No justification has been provided to explain why it is not viable to retrofit the existing building. The embodied carbon for construction of a new office tower is predicted to be approximately 863 kgCO2e/m2 GIA at completion and approximately 1,385 kgCO2e/m2 GIA over its 60-year life.

I was partner in charge of the design of 55 Bishopsgate project (at Fitzroy Robinson) between 1987 and 1992. The design carefully respects and responds to Mewes and Davis’ Grade II-listed Hudson Bay House (Nos 52-68 Bishopsgate) opposite.

In accordance with the City’s plot ratio restrictions at the time, 55 was kept to five principal storeys above ground and its two upper storeys step back in loggias and balconies so that the design does not overshadow its neighbours. It incorporates a subtle curve into its plan to mirror the slight bow in the elevation of Hudson Bay House, across the street and to strengthen this narrow point in Bishopsgate and minimise the visual impact of the building on the St Helens Place conservation area opposite.

The effect on townscape views will be significant and harmful

We decided that the scale and massing of 55 should provide breathing space between the National Westminster Bank Tower (now Tower 42) and the 99 Bishopsgate tower; both buildings will be subsumed by the proximity of a 63-storey tower. 55 Bishopsgate received favourable coverage in the architectural press at the time and I am pleased the Twentieth Century Society is supportive of its retention.

Furthermore, I am very concerned about the harmful effect a tower will have on important townscape views from the nearby Bank, St Helens Place, Finsbury Square and Bunfield Fields conservation areas. From my initial review of the photo-montage views available, the effect on townscape views will be significant and harmful.

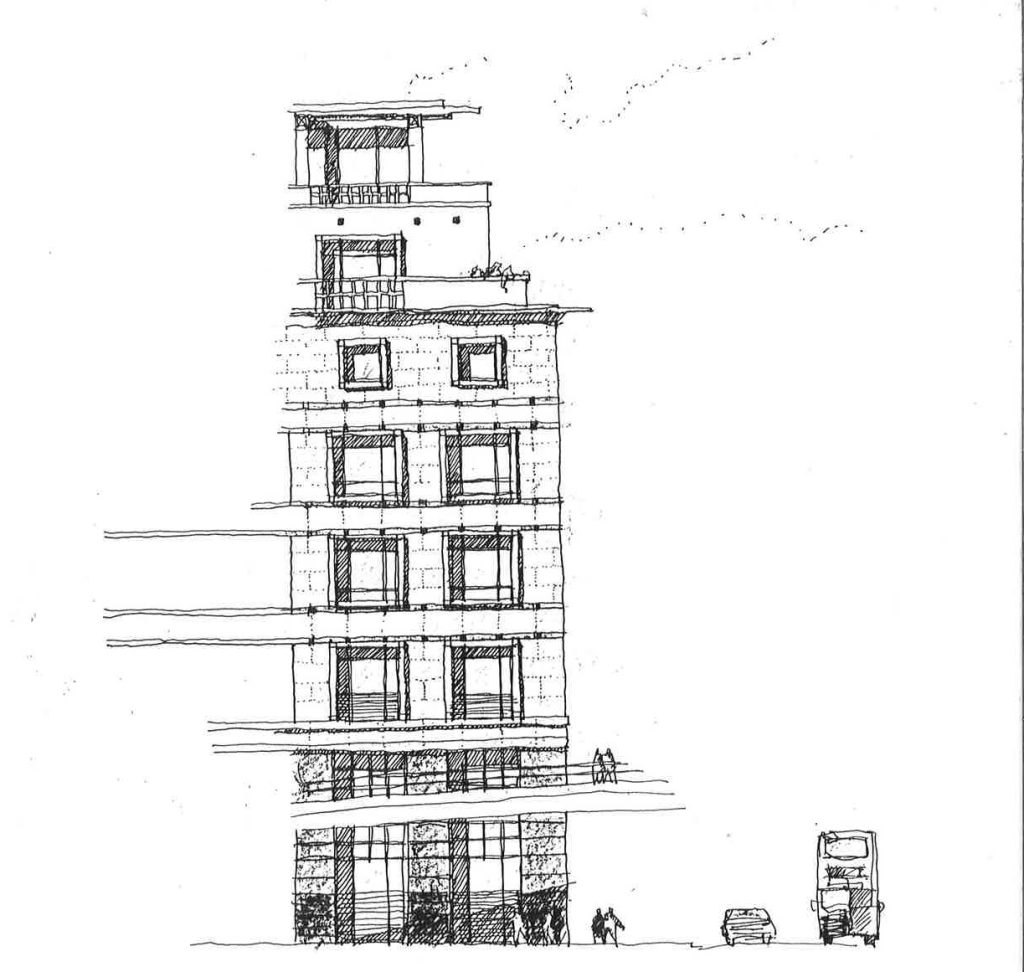

Original sketch of Fitzroy Robinson’s 55 Bishopsgate building

Response by Earle Arney, chief executive and founder, AFK

Why is the existing building not being retrofitted or extended?

As an architectural practice, we are focused on low-carbon design and have a diverse portfolio including retrofits and Rome’s first zero carbon urban campus. Our approach at the outset of every project is to test the adaptability and reuse potential of any existing building on site. We are committed to this methodology and well understand the potentially significant embodied carbon savings of such an approach.

Schroders approached us in 2018 to participate in an architectural competition, inviting us to propose both the adaptive reuse of the existing building as well as an alternate redevelopment of the site, aligned with current planning requirements. As winners of this competition, over the course of the past four years, [we undertook] extensive modelling and wide-ranging studies … to test the viability of retrofitting the existing building. These included looking at operational life, tenant attractiveness and whole-life carbon, together with an assessment of the civic contribution that could be delivered through either retrofit or redevelopment approaches.

Wide-ranging studies have tested the viability of retrofitting the existing building – it could not be justified

Overwhelmingly, these studies showed that a retrofit could not be justified, given the way in which the City and the rapid advancement of both technology and city-making approaches since the completion of the existing building some 30 years ago.

What is the impact of the building from a heritage and townscape standpoint?

A great deal of research and testing is undertaken and required by the City of London as part of the planning application process to build in the City. This particular planning application was perhaps subject to more scrutiny than any other tall building of recent years, due to being on one of the last remaining ‘Opportunity Sites’ in the Eastern Cluster, deemed appropriate to deliver tall buildings

A key part of the work to deliver the proposal for 55 Bishopsgate over the last few years has been the preparation of the Heritage, Townscape and Visual Impact Assessment (HTVIA) prepared by Montague Evans. The assessment of the building is set out in detail in the HTVIA and includes a comprehensive heritage and townscape impact assessment and a rigorous views testing analysis – all completed in close consultation with the City of London Corporation.

This assessment, analysis and consultation process has helped to shape the building design in terms of its form and materiality. The resulting HTVIA assessment demonstrates how the building will have a positive effect on the composition of the Eastern cluster and adds to strategic views across London as well as its relationship to adjoining and nearby heritage assets. It also demonstrates that the proposed development will not result in unacceptable harm to the historic environment and will also deliver significant townscape and urban design benefits that will contribute to the vital activities of London’s commercial centre.

Does the existing building contribute to the city?

After establishing that the existing building could not viably be retrofitted, and redevelopment did not create harm to the historic environment, we were tasked with creating a design that responded to the City of London’s masterplan to increase the experience of this part of the city.

The site is within a Renewal Opportunity Site, the City’s Central Activities Zone of London, and the Eastern Cluster Policy Area. A key statement within the strategic policy is the desire towards ‘enhancing the streets, spaces and public realm to improve connectivity into and through the cluster, and prioritising pedestrian movement during the daytime in key streets such as St Mary Axe, Leadenhall Street and Lime Street’.

The proposed development addresses the City’s objectives by raising all lobby and office functions above the street level to release the ground plane entirely for use by the public, and to include an urban pocket park. This also significantly enhances the permeability through the site, and enables much-needed future east-west and north-south pedestrian routes to adjoining developments that would not be possible should the existing building be retained. By comparison, the existing building delivers 645m2 of public realm, which is a fraction of the permeable public space that will be provided by the redevelopment of the site (5,700m2).

Notwithstanding this nearly nine-fold increase in places for people, we have also designed the public spaces with our landscape architects to ensure they are socially and economically inclusive, and at the same time deliver tangible community value and benefit.

SUBMITTED: Arney Fender Katsalidis’ plans for a 285m skyscraper in the City of London

Source:Miller Hare

Is there an opportunity to elevate the civic contribution of the site?

When designing our cities, we need to think beyond the building scale. As such, providing safe, free public places for people within the City is vitally important and supported by the City’s policies and initiatives such as Destination City.

Since the existing building was completed, many factors have come into play, such as residential population growth within the city, and a greater focus on active travel and enhancing pedestrian comfort and the experience of the City, especially along this important city thoroughfare.

In our design response, we have set the wall of the building back from the boundary and widened the footpath to create a sheltered publicly accessible colonnade along the entire street frontage, which is currently constrained by the existing building. Together, these civic gestures and new public spaces contribute to the City’s aims of becoming a world-leading destination for those who live, work and visit the Square Mile.

When assessing the civic contribution and sustainability of a new proposal it is extremely important that we consider the scales of both the individual building, and the wider city context. We also need to take into account how a proposal is able to leverage the carbon and capital already invested in urban infrastructure.

It will be a building open to everyone

The City of London does not stand still. Its vitality is encouraged by a willingness to embrace proposals that have been rigorously tested, responsibly designed, and which contribute to maintaining its position as a global capital.

I have long argued that the city is the most sustainable construct we have, and densification in areas where mass transit and city infrastructure is concentrated is an environmentally responsible approach.

The redevelopment of 55 Bishopsgate has been approached with these parameters in mind. It will maximise the potential of this prime location in the heart of the City, as well as the transport and amenities on its doorstep, providing a significant increase in workspace to help underpin the economic sustainability of the City.

It will also make a significant civic contribution to the area by putting people first: from the building’s users to those living and working in the City and the millions who visit every year – and most of all, it will be a building open to everyone.

Project data

Location City of London

Local authority City of London Corporation

Type of project Commercial

Client Schroders Capital Real Estate

Architect/principal designer AFK Studios

Landscape architect Townshend

Planning consultant DP9

Structural engineer Robert Bird Group

M&E consultant Hilson Moran

Quantity surveyor alinea

Lighting consultant Speirs + Major

CDM Harwood

Main contractor Not appointed

Contract duration five to six years

Gross internal floor area 126,500m²

Total cost Approx £600 million