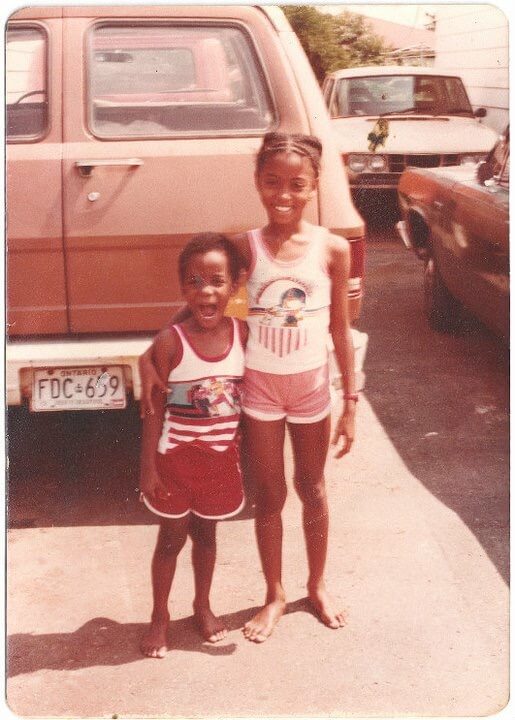

Nina Cooke John and Sekou Cooke are architects who lead independent practices and academics with decades of teaching experience. Nina is the founding principal of Studio Cooke John Architecture and Design, and Sekou leads sekou cooke STUDIO and is the director of the Master of Urban Design program at UNC Charlotte. They are also siblings: Nina is the eldest.

In this interview, AN’s executive editor, Jack Murphy, spoke with them to learn about their pathways in architecture. Their parents, Leroy and Cynthia, joined the conversation to share about their family’s life together.

AN: Nina and Sekou, what was your family life like growing up in Jamaica?

Sekou Cooke (SC): We were inquisitive and argumentative; we were always discussing ideas and concepts. Both sides of our family are big, and they’re each loud in different ways. My father is one of seven, and my mother is one of nine. It’s rarely just the four of us; usually there are more people around, so it is always lively.

Nina Cooke John (NCJ): Our nuclear family is a small part of our influences. As Sekou mentioned, we spent a lot of time with our cousins, uncles, and aunts growing up. Both sides had profound influences on us—my mother’s side of the family includes artists, and my mother’s father was a contractor and used to invent things, keeping his designs in a sketchbook. Also, one of my mother’s sisters was a dancer.

SC: I was going to bring up my mother’s father. Cynthia was talking about how he used to design things and build things for people’s houses and draw them; that’s something I learned recently. I have long thought about architecture as something that requires equal parts of your left brain and right brain. I feel like my father’s influence is more the left brain and my mother’s is more the right brain. That may have been the secret sauce.

AN: How did you both become interested in architecture as young people?

NCJ: Architecture wasn’t on my radar for most of my childhood. But I remember, while in high school, someone describing a house they had visited that was an architect’s house and how amazing it was. That piqued my interest in architecture. I started taking evening classes at Jamaica School of Art, and then my uncles that lived in New York City said, “Oh, City College has a good program,” so I went there before transferring to Cornell. The program was very conceptual, and I absolutely loved it, which is the opposite reaction experienced by many people who go into architecture school expecting to start designing buildings right away.

SC: I was also one of those kids that would take my toys apart and break everything to see how it works. By the time I was five, my grandmother had told me about architects. “So there are these men (as she called them) that draw houses and buildings,” she said. So, architecture became my default answer to the question of what I wanted to do when I grew up.

AN: Leroy and Cynthia, what could you add about Sekou and Nina? What was your household like, and how did it create the foundations for success? Leroy, you were a politician in Jamaica, so I’d be interested to learn more about your work.

Leroy Cooke (LC): They were polar opposites: Nina was laughing all the time, while Sekou was crying. I don’t think the politics affected either of them that much. Nina was more involved, but by the time Sekou was old enough to be aware of what was going on, I wasn’t directly involved in politics.

Sekou was a strange kid, but he was very good at school. He liked to watch TV all the time, which was strange for me because there was no television in Jamaica when I was growing up. He was interested in art, which I remember well because it was different from me. I am the opposite of a gifted artist; I couldn’t even draw something to represent it in a recognizable way, like in geography, where you have to draw a map. The only place I could draw was Barbados! I can definitely tell you that they didn’t get any of their artistic gifts from me.

Cynthia Cooke (CC): Nina was a perfect child. She was mature beyond her years. As it relates to the politics, she was out and about with us campaigning. And even before she was five, she was telling children in the area about South Africa and apartheid. She was quite conscious and listened to the radio to learn what is happening around her. When she heard that architecture could mix art and science, then she chose it to study.

With Sekou, on the other hand, since he was born, he was watching Sesame Street and talking about architecture. He was always looking at buildings and being interested in the shape of roofs and so on. Every summer I had to buy him one of those 64 packs of crayons. He was interested in everything.

Personally, I used to draw, paint, crochet, knit, embroider…all sorts of crafts. I was never interested in being a specialist; I just could do everything. I was sort of carried away into these things. If I had a choice, I would be doing art. But because I was good at mathematics, they felt that I should be doing mathematics and so on. What I enjoy doing is more creative, like making clothes and writing. But because I could do other things, I was pushed that way. So maybe they got the interest in architecture from me, or maybe it came from somewhere else.

AN: Once you finished your respective undergraduate degrees, what did you want to do next?

NCJ: I think I knew that I wanted to continue to be engaged in the academic exploration of architecture, which is why I went back to graduate school after two years of practice. I already had a five-year professional undergraduate degree, so I didn’t need to go to graduate school to become licensed, but I knew that being able to work through theoretical ideas in the academic space was exciting and important to me.

SC: Continuing with the theme of Nina and I being very different, when I left school I thought I never wanted to go back to school. I wanted to learn the business of designing and building buildings, and I wanted to get as much professional experience as possible. I decided early on that I didn’t want to go to a big firm or work for a superstar. All my friends were going to SOM or KPF or trying to get a job at OMA, and I only applied to firms that had four people or fewer. I ended up spending six years at Michael Davis Architects in Manhattan. They had five people at their largest, and while the work wasn’t flashy, it was well thought out. I learned how to run a practice. I didn’t return to academia for ten years.

AN: Did you two compare work experiences?

NCJ: When I was working at Polshek Partnership, Sekou worked nearby on Hudson Street, so we would meet in the middle for lunch. He was in the same building as 1100 Architect at the time. We would talk about projects in parallel, because we were always kind of at different places doing different things.

SC: At the time, she was at a larger firm doing bigger projects, and I was doing these little apartment renovations, so it seemed like that’s how things were going to go. We also knew a lot of the same people, so it was an interesting time.

AN: Now, it seems like the practices you lead have overlapping concerns relating to public space and cultural memory. How did you decide to work between academia and individual companies?

NCJ: In 2001, I moved from the scale of cultural institutions to residential work while teaching and being a young parent. I had small kids at the time, so that mix worked for me. Then, after seven or eight years, I had a business partner; we both had small children, so much of our work happened late at night when the kids were asleep. I was always thinking about getting back into urban engagement. At the time, the best way to seek out those issues was through competitions. My business partner and I invited Sekou to join us for a couple of the entries, including one that I still show all the time, The Power in the Dark.

SC: I’m surprised that our paths aligned so much, because I’ve always thought that we’re quite divergent. But I think that’s due to us being “real architects” who are interested in the entire expanse of what architectural practice can be. It can take on different scales and address different people and communities.

After my office experience, I wanted to work for myself almost immediately and started doing a couple of independent commissions. I started collaborating with some friends from Cornell like Olalekan Jeyifous and Anaelechi Owunwanne. Also, Efrain Perez and I collaborated on a restaurant called Fanny in Brooklyn.

Transitioning to teaching was a surprise at first, but maybe my mother would say that I’ve been doing it my whole life. After four years in California and separating from my wife, I ended up teaching at Syracuse and then going to graduate school at Harvard.

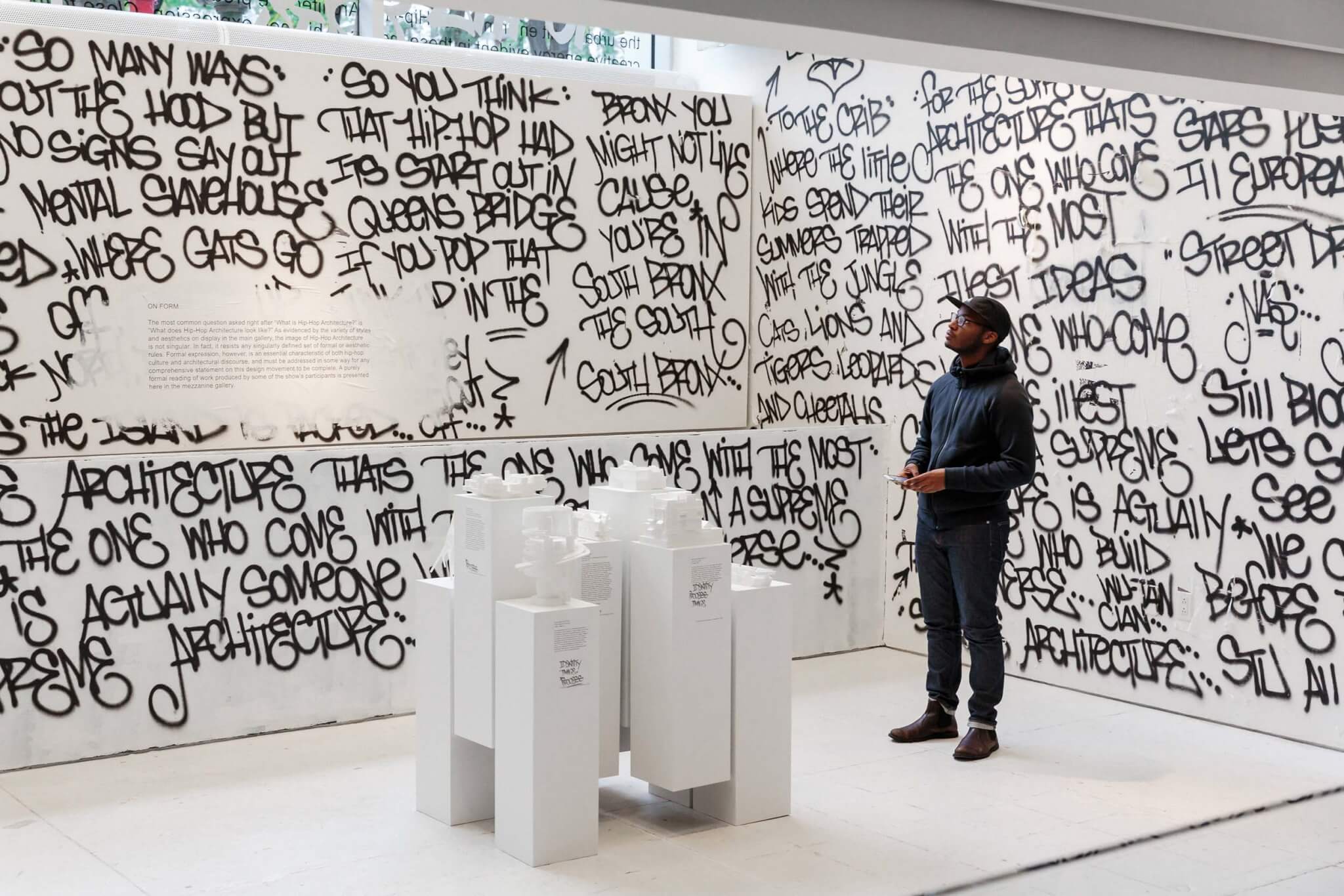

My experience at Harvard is what ignited my current career trajectory. It changed everything. It really made me refocus on larger issues in architecture and understand the importance of research, both in the academy and the larger public. Plus, it allowed me to make connections with influential people. Of course, that was during the time Kanye West visited the school; I coauthored the letter inviting him, and I ended up writing about him. That was actually the spark that led to my work on Hip-Hop Architecture.

AN: Can you say more about the shared interests of your respective practices?

NCJ: My undergraduate thesis at Cornell was sited in the Bronx and Brooklyn and investigated how Jamaican immigrants reclaim leftover spaces and how we could program them for community engagement. I continue to have an interest in the public realm and issues of immigration. Also working on small-scale interventions. That all went on hold for about 20 years. When I give lectures now, I show my thesis project all the time because it is directly linked to a lot of the public installations that I’m doing currently.

While I was in school, I worked best when making physical models, while Sekou was always creating expressive drawings. That is his way of thinking through ideas. In a way, our practices relate to the media we used to explore critical questions: I am now, finally, moving back into working at the scale of the installation, and, Sekou, you’re often working through drawing and images. Is that right?

SC: That’s accurate. I often talk about Nina’s work; I’m also a curator, so I like collecting things and seeing how people arrive at the same idea. When I did my first exhibition on Hip-Hop Architecture, I recommended Nina for the advisory board, and I was also thinking about her thesis project. And now, I’m talking about her Tubman Memorial and her project in Alexandria because I want to have a larger conversation about all of the contemporary practitioners who are hitting this same topic. She’s a big part of that conversation, and I’m always looking at her work with admiration.

Both of us are also in this amazing text group with other people we met at Cornell. It started in 2019 but intensified in the summer of 2020 after George Floyd. This group chat has sustained me for a long time. It has been a space for us to reflect on each other’s work, celebrate each other, share things, or just talk shit about stuff. It has been a really good and powerful tool for over three years, and those have been some of the most interesting times in our careers.

NCJ: What’s great about that group chat is that while we were all undergraduates at Cornell around the same time, we all have different ways of practicing architecture. A few of us have what might be considered traditional architecture firms, but someone else is primarily doing art, though with an architectural influence. Another friend is an arts educator and artist. The group chat is valuable because we arrive at different conclusions, but we share a common ground. We can all talk the talk, and we know the language, but we each have different takes on it.

“This is still architecture” is what we say to people who go to architecture school and think they’re a failure if they’re not practicing architecture afterward. Not everyone who goes to law school and graduates ends up practicing law. Students should know that the skills they learned in school are going to be valuable for any number of pathways that they might choose.

SC: That dovetails with what I’m advocating for these days. This idea is actually at the heart of my second book, Black Architect, which I’m currently writing. It’s about how people—and especially Black people—have a broader sense of what architecture is, what it can be, and what it can be used for. As a profession, architecture is so restrictive; it’s almost like it’s afraid of losing itself. But architectural practice can look like almost anything.

The idea is especially powerful for people who study architecture and don’t see themselves reflected in it because our profession started out as a pastime for wealthy white males. It’s hard to see yourself in there, so it pushes a lot of people out, but that doesn’t mean those people don’t belong or can’t add to the conversation.

AN: Leroy and Cynthia, how do you see your children as adults? What do you think about their successes?

LC: I’m glad that they’re getting public recognition, and I’m even more pleased that they both seem to be happy with what they’re doing. While I didn’t pass on any artistic skills, I feel myself to be intimately interested in architecture, in all senses of the word. I see myself as something of a social architect, in terms of designing and improving a society. I am more interested in public architecture and city planning and improving the conditions in which people live. Jamaica was a British sugar colony, and the British didn’t pay much attention to how cities looked, in comparison to the Spanish and the French. So, I want the country to pay more attention to public architecture.

CC: I was always amazed by my children’s uniqueness. I compare them to others, including the thousands of students I’ve known through my work (as a teacher of mathematics and principal of a coeducational high school of 1,400 students). Whenever I hear something about my children, I want to wake the town and tell the people. I don’t think they want me to do that, but that’s how I feel. Sometimes when I see their successes, it’s sort of like an out-of-body experience, as I see myself in what they do. For instance, I read an article that Nina wrote, and it sounded exactly like if I had written it, even though Leroy is the one known for his literary skills.

SC: Related to family creativity, I want to mention my father’s book, Land of My Birth: A Historical Sketch of the First Forty Years of the People’s National Party of Jamaica. It started as a historical sketch of a political party, and it turned into a book.

CC: Leroy was asked to write something for the 80th anniversary of the party. I couldn’t understand why he was so involved and obsessed with this writing, but he finally showed it to me. I thought it sounded like a book, and he eventually decided to publish it. But of course every time we went back to the computer, there was a new version.

SC: His book came out before my book, Hip-Hop Architecture. That timing was a surprise, but it was good because then he was available to do my index. For his own book, he did everything except printing—pagination, index, editing, all of it.

We should also acknowledge the fact that during this conversation, our parents are sitting in a house in Jamaica that Nina designed.

NCJ: With a little bit of help from Sekou!

AN: Can we talk about this house? What was it like to have your parents as clients?

NCJ: It happened a long time ago; I think the house was finished in 2001, and my parents moved in in 2002. They were good clients. For me, it’s all about how to create a space that works best for the people who will live there. I knew there would be family events with many people over, but it also needed to work when it was just the two of them: Leroy needs a small study that was distanced from the TV room, and things like that. There are several things that I might have done differently, but in terms of the layout, I’m happy with it.

CC: We wanted high ceilings and lots of light. I didn’t ask for anything else.

LC: We were willing to be the guinea pigs. Nina wasn’t able to be present to guide the construction, so I think that was a slight minus.

SC: I was still in undergrad when Nina started, but by the time construction began, I was out of school, so I helped lay out the kitchen and designed some doors and windows.

Thinking back, my parents were good clients because they were able to be expressive and clear about what’s important and flexible about what isn’t, which allows the designer to have agency, which is what we need from all of our clients.

LC: I had faith in Nina. I trusted her in terms of what she would design. It was the first house to be built in the area, and other people were awestruck by it.

CC: Everybody wants to come and look at the inside. Twenty years later, maybe the stairs need to be rebuilt. Nina wasn’t here, so I had to design them myself.