Our initial approach was for a fabric-first strategy to upgrade building envelopes and increase operational carbon efficiency. Unfortunately, quite early on it became clear the budget wasn’t sufficient to fund major works to external envelopes and so we knew we were dealing predominantly with internal refurbishment, service upgrades and trying to maximise what we could do internally.

We also upgraded the wifi and internet systems to allow people to work anywhere in the building and extended that to the new first-floor café for those people who might come to the campus for just an hour’s meeting but want to sit there before or after.

South elevation of Building 16, FCBS’s 1996 building on the BRE campus

How did you look to maintain the spirit of the original when upgrading and changing the building fabric?

But the pandemic presented a significant change. With the introduction of flexible and hybrid working, BRE was keen to focus on the collaborative side of working. We worked closely with them on furniture provision and layouts for each office floorplate to provide different workspace types and configurations, which, in effect, they’re testing to see which are more subscribed to or used.

Creating a variety of workspaces

Was there anything about your original building (FCBS’s Building 16) that didn’t work?

We were tasked with defining where operational carbon reductions could be made. We then needed to set a target as part of the Hertfordshire Local Enterprise funding on both embodied and operational carbon reductions. These were set at RIBA Stage 3 as part of the requirements.

We started looking at internal blinds to reflect heat back out and at making these work in conjunction with window openings. For instance, in Building 17 you have traditional lower casement and upper casement openings. In summer you open the lower casement to get a breeze through and cross-ventilate the building and then in winter you close that and open the upper casement to avoid cold draughts but still get ventilation. But we discovered many occupants didn’t know how to use these.

So, while QR-coding or digitally tagging items is a great idea, a lot of time could be wasted tagging items that aren’t able to be re-used, so perhaps that process should happen after the demolition phase, once you want to reimplement those materials.

We also focused on the refurbishment and re-use of existing furniture. We then defined which items were fit for purpose or what form of restoration would be required to enable their re-use.

So you were able to re-use elements such as carpet tiles?

Project data

Can you briefly outline how you refurbished the furniture?

There was some basic energy performance data for both buildings, as BRE monitors its own energy consumption. This was a useful starting point for looking at reducing operational carbon and highlighting where the issues were – such as heating systems. We started the project almost a year into the pandemic, so both buildings were empty. We therefore had limited ability to question occupants about how the building was failing, so this was more anecdotal. But BRE had compiled a really useful survey of employees covering environmental and comfort control shortfalls in each building: predominantly issues with glare, heating and ventilation.

We initially looked at four buildings on the estate, ranging in age from the 1950s to our own building from 1996. The two buildings we highlighted for the initial phase of refurbishment – BRE is looking to refurbish the other two in the next few years – did present different design and refurbishment challenges.

Existing tiles repurposed in acoustic rafts for Building 17

Building 16 had aged pretty well in terms of providing flexible office floorplates. We opened up some cellular office space on the ground floor to make it more lettable for the innovation hub. The subsequent refurbishment was relatively light-touch: upgrading lighting, looking at some operational issues, replacing floor finishes and giving it a light refresh throughout.

The furniture, fixtures and equipment budget in particular was really challenging, so it was a given that re-using existing furniture where possible was a priority. Similarly with the ceiling tiles. There was no defined budget for acoustics, so when developing our strategy to meet the requirements for the office space in terms of reverberation time and clarity of speech we realised we needed to re-use existing tiles, reconfigure these into acoustic rafts and deal with the acoustics like that. So, in some ways, the cost constraints helped drive and prioritise sustainability agendas.

Has this led you to be more critical about the flexibility of other FCBS buildings?

The refurbishment has been relatively light-touch: upgrading lighting, looking at some operational issues, replacing floor finishes

Did this help you not to be too precious with the original building?

Between 1996 and the pandemic, the biggest change was probably the shift from cellular to open plan working.

Then we put in place a strategy that co-ordinated with BRE’s new branding to determine a colour palette range within which the chairs could be refurbished. Once re-upholstered with a range of fabrics in a coherent colour palette, the fact that all the chairs are slightly different didn’t matter: they hang together quite coherently.

These included individual traditional task-based desks in an open plan office setting, counter-height desks and chairs for group work and collaboration, more informal lounge-type workspaces for collaborative meetings, and acoustically separated booths for virtual meetings as well as traditional separate meeting rooms for more private team meetings. We also looked at hot desk opportunities on each office floor and in the café.

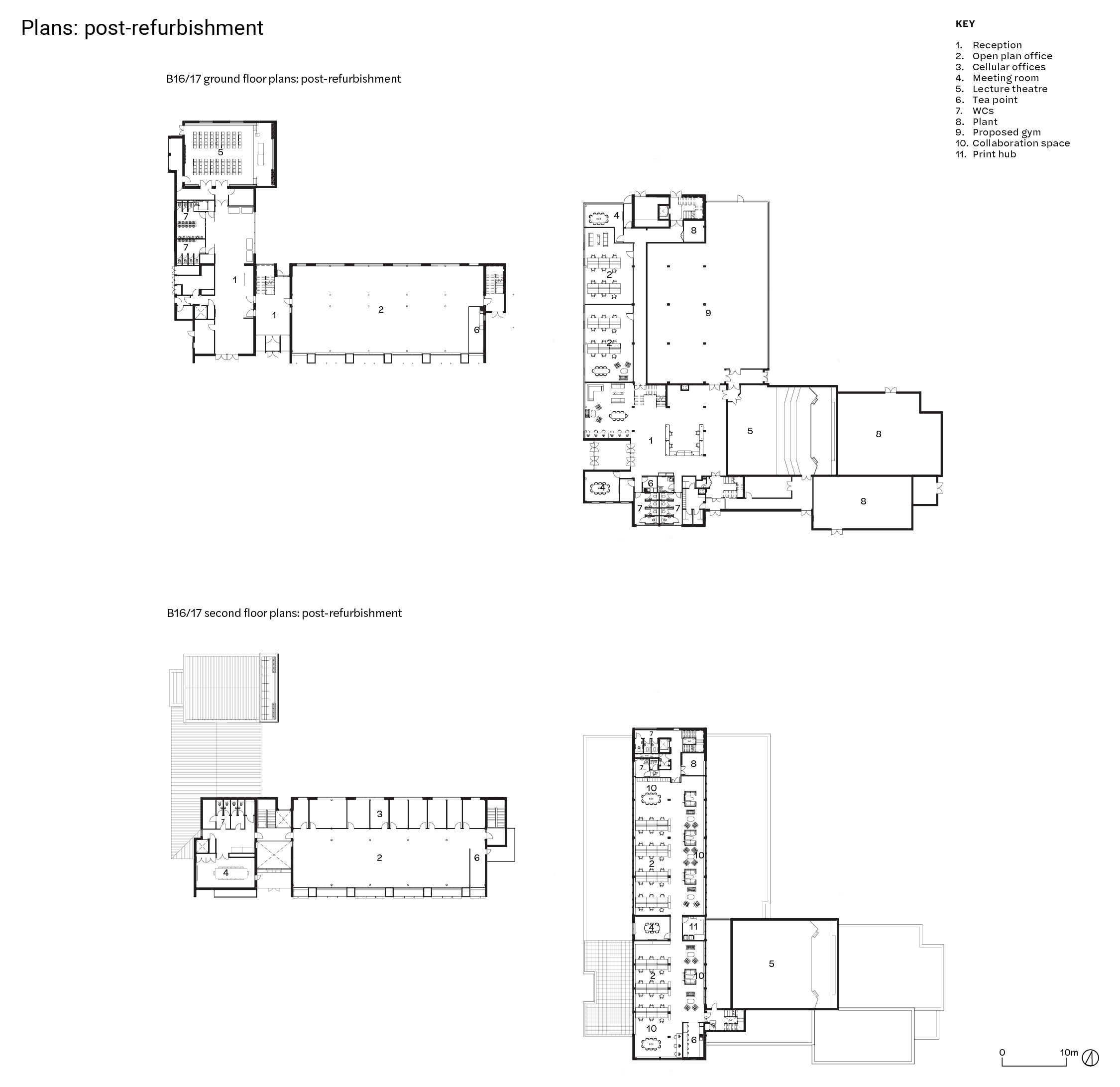

Building 16 second floor post-refurbishment