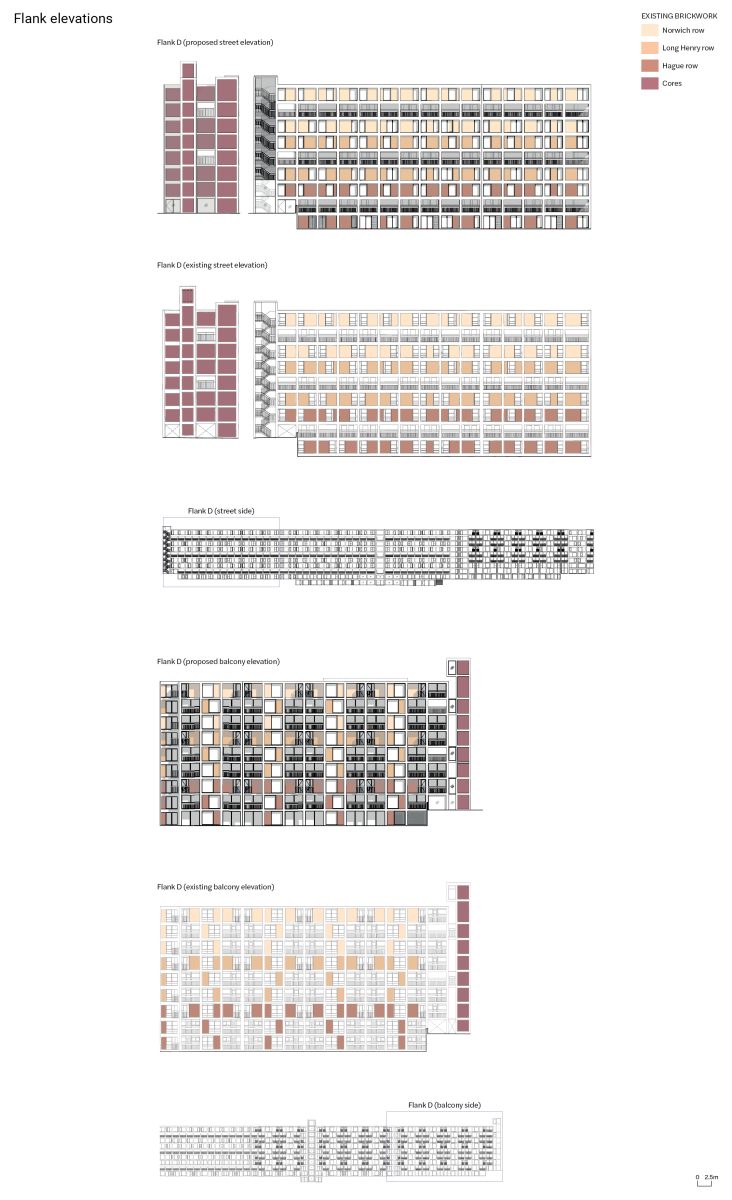

We spent two weeks looking at the building, studying it and learning from Phase 1. We noticed the remnants of lives lived there, the traces of inhabitation and how residents had made their flats homes. Some had painted their balcony cheeks different colours, all had laid patterned linoleum on their doorsteps. We won the competition with our proposal: to faithfully restore the building keeping as much of the existing fabric as possible, upgrading it thermally and acoustically, and giving each flat its own identity using patterned doormats and coloured balcony reveals.

It was another milestone in the life of a scheme that has remained one of the lodestars of UK post-war housing since being built and a bellwether of attitudes to them.

Mikhail Riches’ sensitive picking up on and referencing of clues offered by the existing fabric has been a feature of its nuanced approach throughout the project.

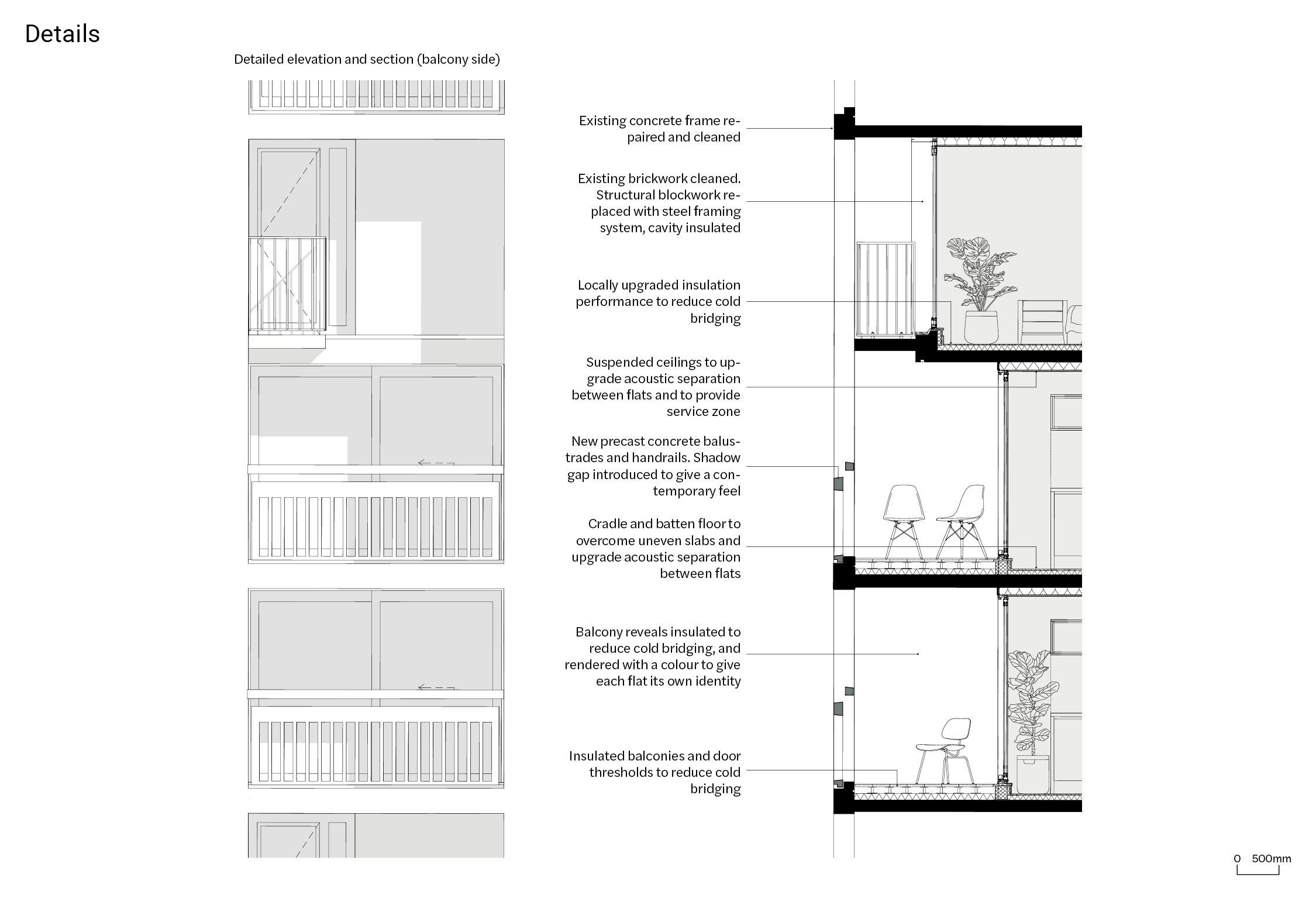

Internally, rooms have been lined like ‘insulated boxes’– with insulation added to the cavity wall brick panels, windows moved back into thermal line and balcony flank walls and the soffits of living spaces all lined in insulation. The latter, while aiding with acoustic separation and providing a concealed service zone, also results in an unfortunate squeezing of head height, given the already low floor-to-floor dimensions of 2.515m, to just 2.215m.

Repair mortar and an anti-carbonation coating was applied to all exposed concrete elements. The aim of this coating was to provide a barrier to mitigate further carbonation and extend the design life of the superstructure frame.

Park Hill is an exposed concrete frame building. Its Grade II*-listed status means that overcladding the concrete, which acts as a massive cold bridge, was not an option; we needed to insulate both sides of the concrete in each room.

Completed in 1961 by Sheffield City Council, Park Hill is a Grade II*-listed Brutalist housing scheme, containing 1,000 homes, making it Europe’s largest listed structure. Urban Splash took on its redevelopment and Phases 1, 2 and 3 are now complete.

Civic Engineers acted as civil and structural engineer on Park Hill Phase 2 for Urban Splash. Having provided the same service and support on Phase 1 (2007-2011) and Phase 3 (2017-2020), Phase 2 saw our role evolve as we designed a retentionist repair strategy for the existing concrete frame. The principal design aims of this were:

- To prolong the useful design life of the concrete frame

- To do so in a way that would not permanently damage its heritage importance, which was also in keeping with the proposed façade treatment

- To do so in a way that would provide a durable exterior to gain approval from building warrantee providers

- To maximise the period to first maintenance.

The brickwork has been lightly cleaned externally and insulated internally. New windows are pushed back to the thermal line with pressed aluminium reveals creating depth to the façade, providing some solar shading while giving the brick an equivalent treatment to Phase 1’s brightly coloured panels.

Alim Saleh, senior architect, Mikhail Riches

The only major demolition of the frame has been around the entrance areas, where new double-height lobbies have been created through the removal of flat units. The treatment of these lobbies is much rawer than in Phase 1. There, elements like a shiny sculptural stainless-steel stair were inserted; here, lifts and stairs remain strictly orthogonal and utilitarian, with existing concrete walls left showing all their history, including the cast-in timber chocks used to attach skirtings in the lost flat units.

The listing, while saving the building, threw up extra issues for retrofitting it and making it financially viable for a developer to take it on. Given this, it was agreed, after discussions with English Heritage, that for Phase 1, Urban Splash could strip the structure back to the frame and rebuild from there. The bright-hued ‘look-at-me’ transformation was the result, with the pinkish and buff brick infill panels replaced by powder-coated aluminium. In addition, the previous balance between window and solid wall was inverted, significantly increasing the proportion of glazing on the façade.

Gobsmackingly, it was just one of four huge estates – and not even the largest – planned and built in a ring around Sheffield by Womersley’s team. However, as with many other large Modernist estates in the UK and against a background of deindustrialisation and rising unemployment in the 1970s and 80s, all four estates suffered from lack of maintenance and antisocial behaviour. By the following decade, the other three had been totally or partially demolished. It’s a fate Park Hill might have suffered too but for its Grade II*-listing in 1998, in recognition of its importance as a fully realised version of ‘streets-in the-sky’ and its inspired use of its hillside site.

Source:Left: Keith Collie, right: Daniel Hopkinson

We are also working with low existing ceiling heights: floor-to-floor dimensions are 2,515mm (these would be at least 3,100mm in a modern building) but to achieve the best results thermally within the tight parameters we have added insulation to bring ceiling heights to 2,215mm.

Historic photograph of Park Hill Flats by Sheffield City Architect’s Department, 1961

Architect’s view

‘It’s also incredibly complex – more like a 3D jigsaw puzzle. That meant every corner has had to have a bespoke solution to the wet-cold frame. It would have been so much easier just to overclad it!’

But the completion of Phase 1 undoubtedly remains a signature model for the reimagining and rehabilitation of Modernist estates, both as places to live and in the public imagination. It was shortlisted for the 2013 Stirling Prize at a time when the demolition of other prominent examples, such as London’s Heygate Estate, was gathering pace.

This report was crucial for our performance specification and repair strategy which included removing areas of defective concrete, including cleaning and removal of corroded reinforcement. Where corrosion of exposed reinforcement was significant, bars were locally cut out and replaced with new welded reinforcing bar primed for application of repair mortar.

In 2015 Urban Splash held a competition for Phase 2 of the project: 195 flats and 2,000m2 of commercial space. It gave the five shortlisted practices a flat in the derelict building and two weeks to demonstrate their ideas. The brief asked the architects to ‘spend as much time on the site, live and breathe it, wholeheartedly commit – can you do this?’